Performance, video, Installazione, fotografia. 2024…

Performance, video, installation, photography. 2024…

In English below

Ho conosciuto i travasatori.

Ho conosciuto persone che compiono da secoli atti inutili:

Nel settembre del 2019 mi trovavo ad Ascoli Piceno per le riprese di un documentario. Viaggiavo con un camion, insieme al signor Mario, il conducente, la direzione era Monza. Trasportavamo roccia lavica proveniente da Catania. Quiescenza, terra quieta e trasbordante di omissioni, era il significato di quel nostro tragitto.

In una piazzola di sosta ho conosciuto uno strano gruppo di persone. Anche loro con un camioncino, un po’ più piccolo che trasportava acqua. Non c’era solo quel mezzo ma anche altri, tra auto e moto, che pareva non trasportassero nulla, ma che seguivano come assorti da qualcosa di imperscrutabile quel camioncino.

Questa gente non era molto disposta a soddisfare le mie curiosità. Eravamo solo semplici trasportatori. Loro sin dal primo momento mi son sembrati ambigui, troppa gente per seguire un camion, troppi mezzi che per le mie idee non avevano senso di essere li.

Le persone spesso per sopravvivere tendono ad imitare e competere con entità che vivono al disopra e al disotto di loro. In questo caso, ad Ascoli, ho assistito gente competere contro nuvole, contro il sole e contro la luna.

Il Signor Mario ed io andavamo verso nord, loro andavano a ovest...

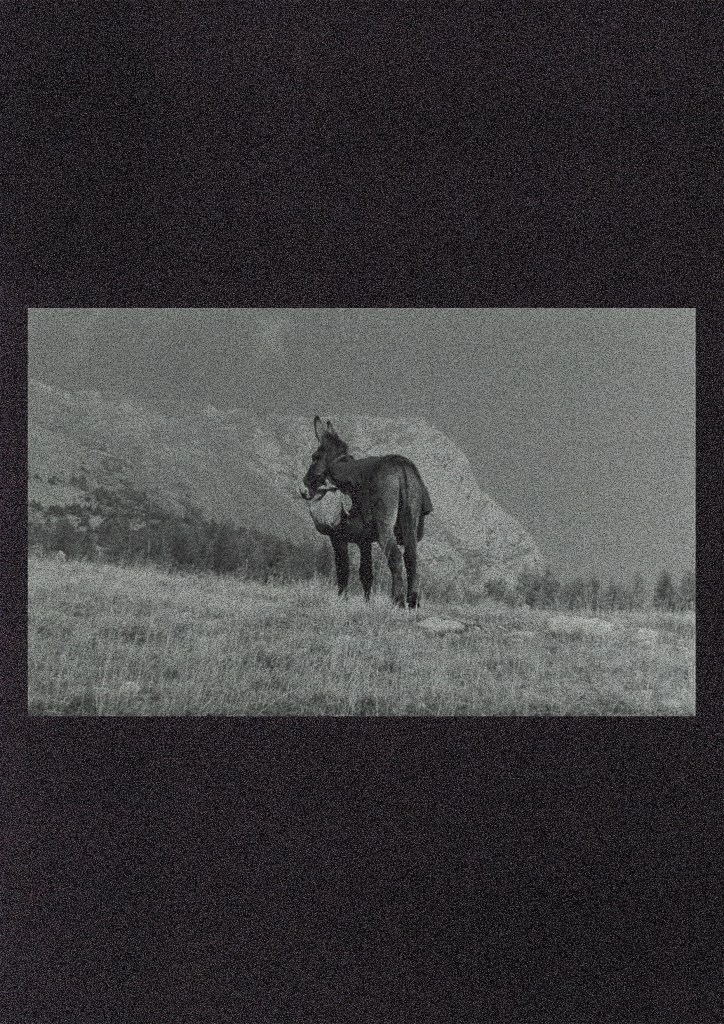

Il Travaso dell’Asina

Le transumanze sono pratiche di lavoro popolare che da sempre hanno contribuito a formulare leggende, tradizione, cultura. L’appartenenza popolare, le varie forme di comunità culturali, sono state nei secoli modellate da saperi indotti con vari metodi di tramando: L’oralità, l’artigianato, le ricorrenze, arte dalla provenienza non identificata. Il pascolo vive in luoghi dove l’influenza delle società così dette “moderne”, fatica ad invadere terreno. Questo, almeno, si spera. Nei luoghi, più specificatamente nell’entro terra, succede che le produzioni culturali della modernità non sono riuscite ad essere totalmente dominanti per le culture secolari o millenarie che li vivono. Esiste però una forma di contaminazione che ha creato mescolanze grottesche che danno vita a nuove tradizioni o ne modificano altre già esistenti.

Il travaso dell’asina è una tradizione centro italiana che perdura da almeno cinque secoli. Questo è perlomeno il sentito dire. Si pensa possa risalire dal momento in cui si è iniziato ad usare in Europa il calendario Gregoriano. Si tratta di una tradizione popolare, tramandata oralmente e pragmaticamente, resistita nonostante i molti cambiamenti culturali, politici, sociali, storici della penisola italiana.

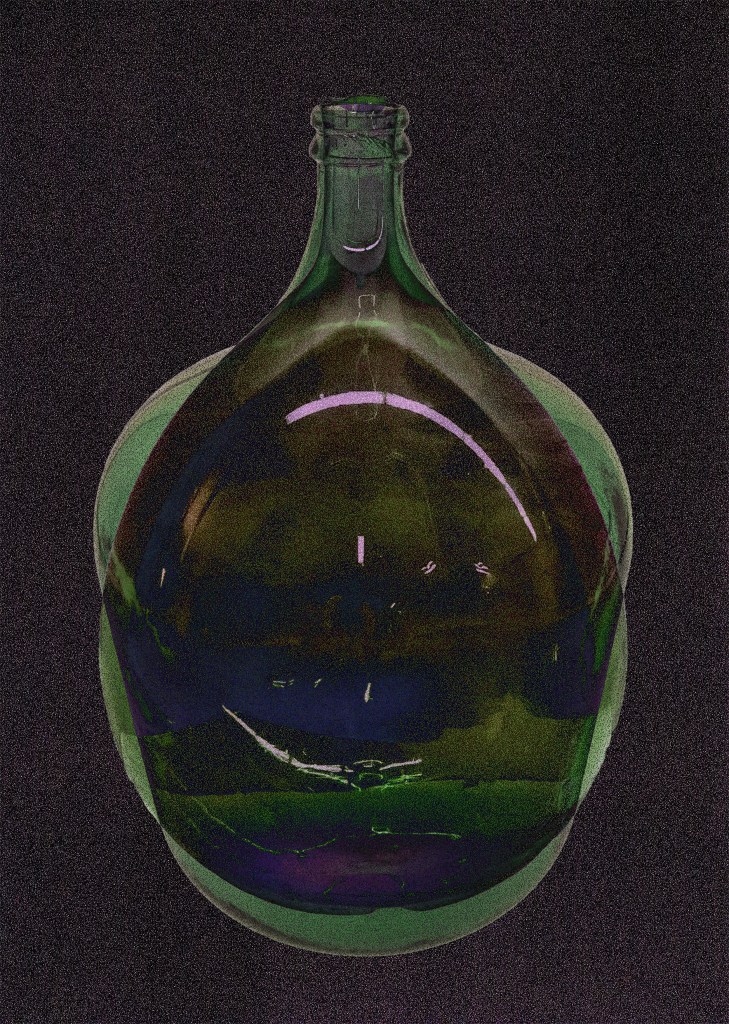

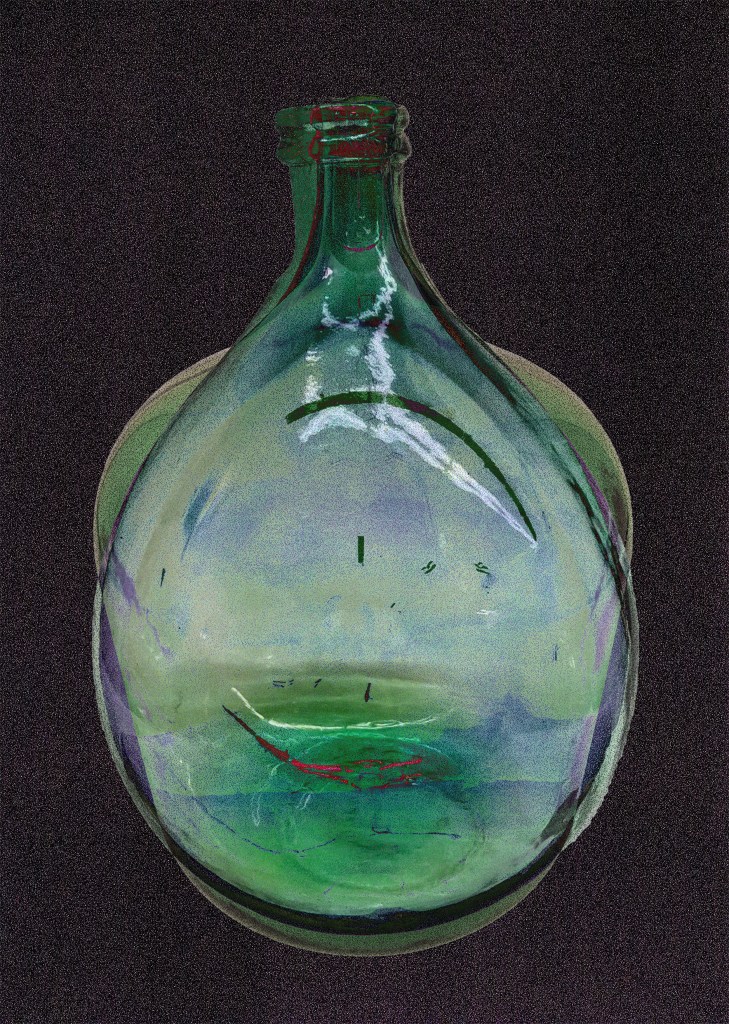

Il travaso è una transumanza che parte dalla costa adriatica e termina nella costa tirrenica. Da Ascoli Piceno, finisce nei pressi di Ostia, costa romana. Si chiama travaso perché consiste nel prelevare acqua dal mar Adriatico e nel travasarla nel mar Tirreno. Lo scopo è quello di una mescolanza dei Sali, delle acque, dei sapori e dei sentimenti. Il tragitto coincide con la vecchia Via Salaria del periodo romano, modificata nei secoli e resa strada percorribile per i mezzi pesanti.

Ad oggi le località coinvolte sono i centri storici protagonisti del tracciato: Porto d’Ascoli, Offida, Civitella del Tronto, Ascoli Piceno, Castel Trosino, Acquasanta Terme, Arquata del Tronto, Accumuli, Amatrice, Leonessa, Monte Terminillo, Antrodoco, Rieti, Sinibalda, Lago del Turano, Monteleone Sabino, Abbazia di Farfa, Frasso Sabino, Fara in Sabina, Monterotondo, Roma, Ostia.

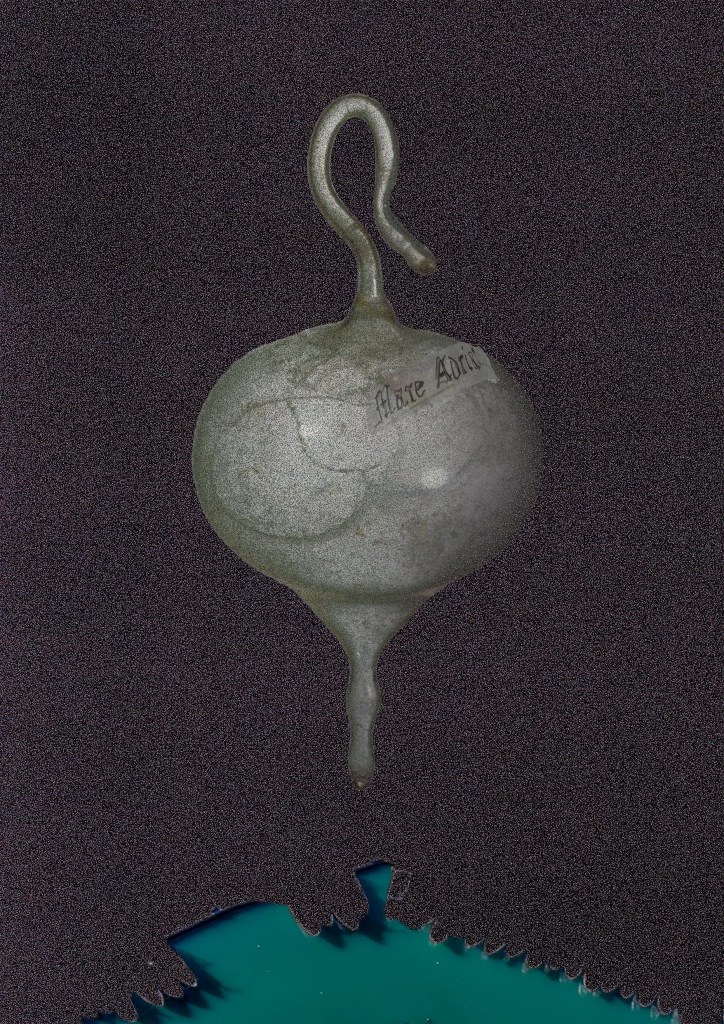

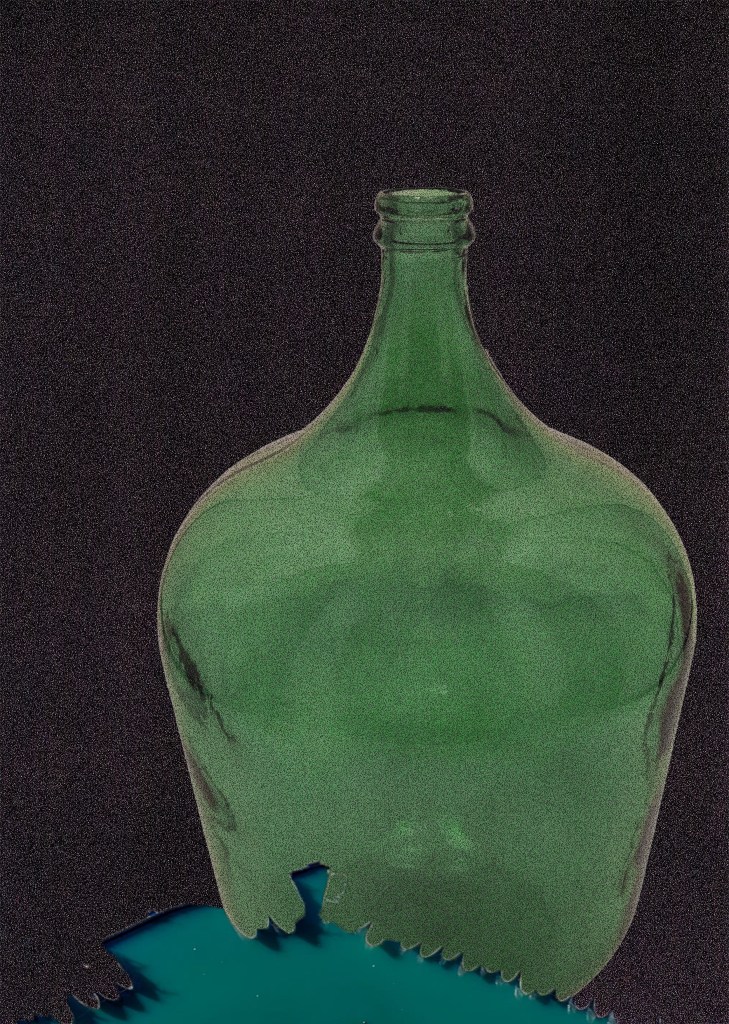

L’asina fu il primo mezzo con cui il tragitto venne intrapreso. Le strade, vecchie mulattiere lungo la via Salaria, antica via romana ideata proprio per il trasporto del sale da Ascoli a Roma. Il tutto percorso con una decina di animali. Dagli anni 60 invece la pratica si è trasformata in un viaggio con mezzi a motore. Oggi si usa un camioncino apposito che trasporta damigiane.

Durante il tragitto si sosta in sette località differenti, fino ad arrivare ad Ostia. In ogni luogo viene effettuato un rituale, di origine pagana, come simbologia transitiva dell’atto. Nell’insieme è una forma iniziatica che accoglie con presagio l’anno nuovo. Questa tradizione normalmente coincide con gli anni bisestili, a seconda delle fasi lunari può variare dall’anno prima o l’anno dopo. La media comunque è ogni quattro anni, solo raramente ogni tre, molto più spesso ogni cinque. È risaputo da varie culture europee che l’anno bisestile sia un anno di sventure. Si narra che le località del Travaso dell’Asina contribuiscano a loro modo a cambiare massa peso e volume del mare, in modo tale che il moto della Terra sia pronto per affrontare meglio l’anno che ha il giorno in più.

La penisola italiana ha, per sua natura, una formazione geologica che predispone all’ideazione di avvenimenti culturali così caratteristici, così in stretto contatto con il terreno e con le sue acque.

Questa tradizione nei secoli è stata portata avanti da una molteplicità di mestieranti: marinai, contadini e pastori, allevatori e artigiani. Gli attori di questo tragitto sono comunemente chiamati “I Travasatori”. A resistere fino ad oggi è un consorzio di comunità locali, quelle che nel territorio Piceno sono chiamate “Comunanze agrarie”. La Comunanza ha l’intento di tramandare il Travaso mantenendo lo statuto originale. Gli ultimi anni non hanno avuto grandi fortune per via di diatribe interne ai gruppi. Il cambio generazionale sta conducendo l’evoluzione del travaso in cambiamenti che preoccupano un po’ le generazioni passate…

Questa storia, come tante storie è leggenda e come tante leggende vuole mescolarsi nella realtà.

I met the decanters.

I met people who have been performing useless acts for centuries:

In September 2019, I found myself in Ascoli Piceno for the filming of a documentary. I was traveling with a truck, along with Mr. Mario, the driver, heading towards Monza. We were transporting volcanic rock from Catania. Quiescence, a quiet land overflowing with omissions, was the meaning of our journey.

At a rest stop, I encountered a strange group of people. They also had a small truck, a bit smaller, which was carrying water. There wasn’t just that vehicle but others as well, including cars and motorcycles, which seemed to be transporting nothing, yet followed that small truck as if absorbed by something inscrutable.

These people were not very willing to satisfy my curiosity. We were just simple transporters. From the first moment, they seemed ambiguous to me—too many people following a single truck, too many vehicles that, to my mind, had no reason to be there.

People often, in order to survive, tend to imitate and compete with entities that live above or below them. In this case, in Ascoli, I saw people competing with clouds, the sun, and the moon.

Mr. Mario and I were heading north, while they went west…

The Decanting of the Jenny

Transhumance has long been a traditional practice of labor that has contributed to the formation of legends, traditions, and culture. Popular identity and the various forms of cultural communities have been shaped over the centuries through knowledge passed down by different methods: oral tradition, craftsmanship, festivals, and art of unidentified origin. Grazing thrives in places where the influence of so-called “modern” societies struggles to take hold—at least, one hopes. In certain areas, especially in the inland regions, modern cultural production has not been able to completely dominate the ancient or millennia-old cultures that reside there. However, there has been a form of contamination that has led to grotesque blends, giving rise to new traditions or altering preexisting ones.

The Decanting of the Jenny is a tradition from central Italy that has endured for at least five centuries—or so it is said. It is thought to have originated around the time Europe adopted the Gregorian calendar, although some theories suggest a much more ancient provenance, dating back to the Italic Spring, the Ver Sacrum. This is a popular tradition, passed down orally and through practice, surviving despite the many cultural, political, social, and historical changes on the Italian peninsula.

The decanting is a form of transhumance that starts on the Adriatic coast and ends on the Tyrrhenian coast. From Ascoli Piceno, it concludes near Ostia, on the Roman coast. It is called “decanting” because it involves taking water from the Adriatic Sea and decanting it into the Tyrrhenian Sea. The purpose is to blend the salts, the waters, the flavors, and the emotions. The route follows the old Via Salaria from Roman times, which has been modified over the centuries to accommodate heavy vehicles. Today, the towns involved are historical centers along the route: Porto d’Ascoli, Offida, Civitella del Tronto, Ascoli Piceno, Castel Trosino, Acquasanta Terme, Arquata del Tronto, Accumuli, Amatrice, Leonessa, Monte Terminillo, Antrodoco, Rieti, Sinibalda, Lago del Turano, Monteleone Sabino, Abbazia di Farfa, Frasso Sabino, Fara in Sabina, Monterotondo, Rome, and Ostia.

The jenny was the first means of transportation used for the journey. The roads were old mule tracks along the Via Salaria, an ancient Roman road specifically designed for the transport of salt from Ascoli to Rome. The entire journey was completed with a dozen animals. However, since the 1960s, the practice has transformed into a journey using motorized vehicles. Today, a specially designed truck is used to transport large glass containers.

Throughout the journey, there are stops in different locations, culminating in Ostia. In each place, a ritual of pagan origin is performed, symbolizing the transition of the act. Overall, it is an initiatory process that welcomes the new year with omens. This tradition typically coincides with leap years, although depending on the phases of the moon, it can vary by a year before or after. On average, it occurs every four years—only rarely every three, but more often every five. It is well-known across various European cultures that the leap year is one of misfortune. It is said that the towns involved in the Decanting of the Jenny contribute in their own way to altering the mass, weight, and volume of the sea so that the Earth’s motion is better prepared to face the extra day of the year.

The Italian peninsula, by its very nature, has a geological formation that predisposes it to the creation of such characteristic cultural events, deeply connected with the land and its waters.

Over the centuries, this tradition has been carried on by a multitude of tradespeople: sailors, farmers, shepherds, breeders, and artisans. The participants in this journey are commonly known as “The Decanteres.” Today, it survives through a consortium of local communities, known as comunanze agrarie in the Piceno territory. The consortium of these comunanze aims to preserve the Decanting by keeping its original statutes intact. In recent years, however, the tradition has faced challenges due to internal disputes among the groups. The generational shift is driving changes in the decanting process, causing concern among older generations.

This story, like many stories, is a legend, and like many legends, it seeks to blend with reality.